The Rise and Fall of Bagel Bakers’ Local 338

How New York Bakers Formed One of the Most Successful Unions in the 20th Century

"A bagel is a doughnut with the sin removed." - George Rosenbaum

For breakfast, there isn’t a more convenient or delicious option than a bagel. Available in an array of flavors and an endless number of ways to eat them, bagels are a popular choice for over 202 million Americans annually. To many, the bagel is a peak American trend that took off out of the boroughs of 1900s New York and onto the breakfast plates of millions of Americans by the 1960s.

However, for one union, the bagel stood as a symbol of labor rights for immigrant bakers living in the Tri-State area for over 40 years. Seen as one of the most successful labor movements of the 20th century, Bagel Bakers’ Local 338 led the charge for better working conditions in bakeries across Manhattan and its surrounding neighborhoods.

By tightly controlling the bagel market, Local 338’s unionized efforts brought financial prosperity to its members for decades. They helped establish bagels as a popular and in-demand food item—an achievement that ultimately caused their demise.

Bagel’s European Background

Though we can trace bagel’s U.S. roots to the Jewish communities of early 1900s New York, its history goes back hundreds of years to 13th century Eastern Europe. Writer Maria Balinska of “The Bagel: The Surprising History of a Modest Bread” traces the creation of the bagel to Jewish bakers who lived in what is now Poland. She cites that while they lived in lands defined by anti-Semitic laws, these bakers were permitted to make their bread, with the caveat that they also had to make bread for their Christian neighbors as well, something that was not a societal norm at the time.

The most popular of their sold goods was obwarzanek, a boiled, ring-shaped bread that Christians consumed during Lent. While the larger obwarzanek was consumed for special holidays and occasions, a smaller version was baked for everyday consumption. This single serving boiled bread became known as a bajgiel in Polish or beygal in Yiddish. Soon after, Christians also began buying bagels, and their popularity grew with the urbanization of Eastern Europe.

America's Introduction to the Bagel

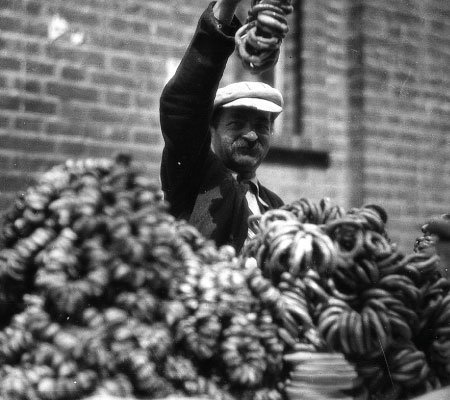

As European Jews began migrating to the United States in the 19th century, so did bagels. As thousands of migrants touched down in New York City, dozens sought to open their bakeries across the Lower East Side, staffing their own to provide challah, rye bread, and bagels for their community.

However, due to overcrowding in these areas, Jewish bakeries gained a reputation as having some of the most unsanitary working conditions in the city. With limited space, many bakers worked in underground bakeries whose environments consisted of vats of boiling water, coal-fire ovens, and infestations of roaches and rats. Described from a New York Press article in 1894, Atlas Obsucra's Natasha Frost cites reporters descriptions of the shops’ rotting foundations as having infestations “of a great variety of insect life” with roaches “springing at a lively rate in the direction of the half-molded dough.”

Workers compared their working conditions as being in “hell,” with rooms reaching upwards of 120 degrees and bakers stripping down to their underwear to continue their grueling work.

With these dangerous working conditions, bakers attempted to advocate for their rights by forming early bakers’ unions, all of which failed.

Until the Local 338 came on the scene.

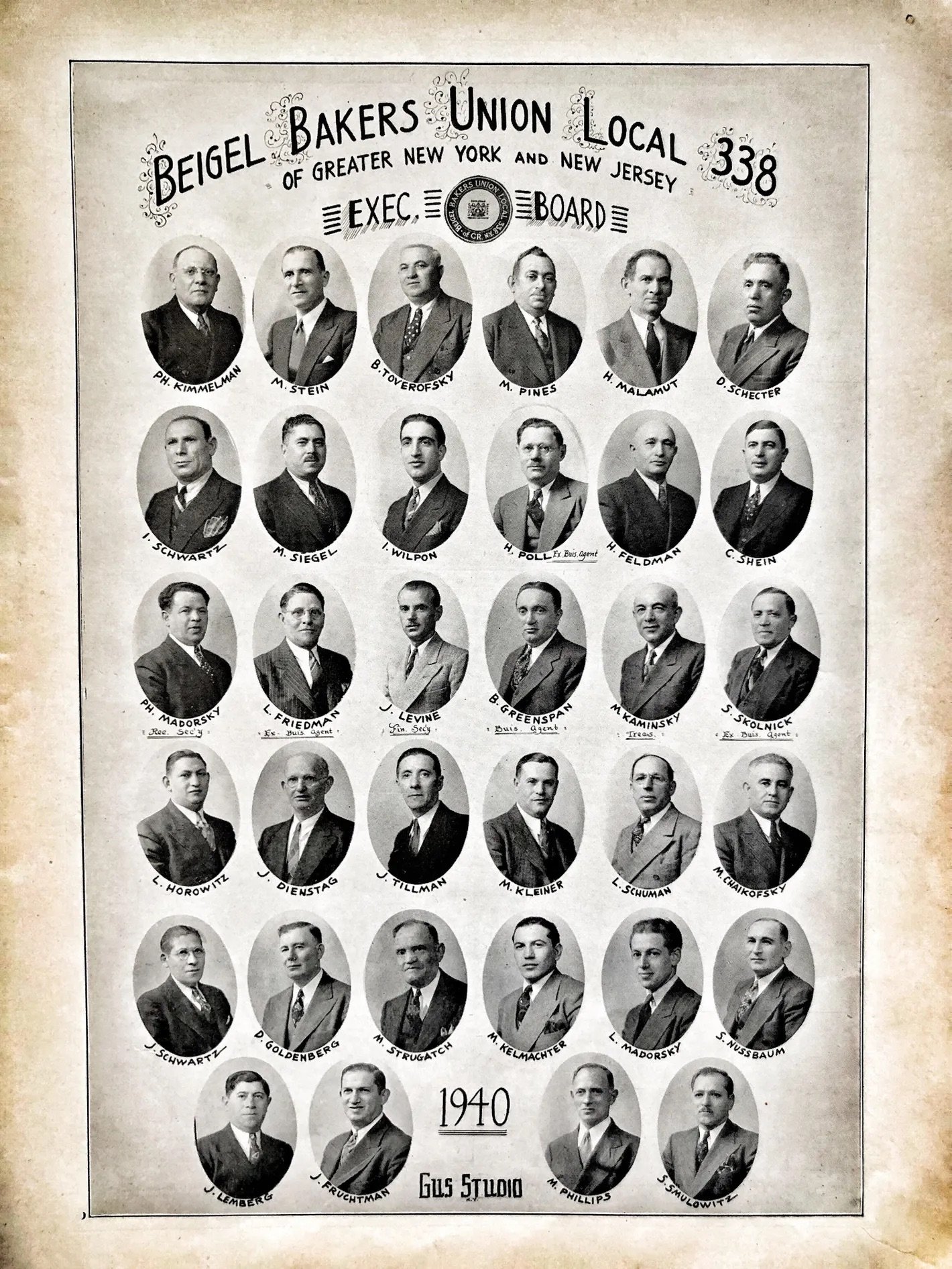

Bagel Bakers’ Local 338

Established in the 1930s, Bagel Bakers’ Local 338 was an organization of 300 Yiddish-speaking members of Jewish descent. These men were macho types fueled by alcohol, coffee, and steak, each with deep roots within the Jewish baking community. Almost all who joined had a direct family connection, keeping membership exclusive only to those who could pass on the old-world, generationally honed skill.

During the union’s creation, bagels were becoming a favorite among Jewish-American enclaves, and within 8 years, Local 338 had contracts with 36 of the Tri-State area’s largest bakeries. Demand in Manhattan and the eastern neighborhoods kept bagel bakers in high demand, and members of 338 steadily rose as artisanal members of their community who crafted a “one-of-a-kind” good.

By obtaining their high status, Local 338 held tight control of the bagel market in the mid-20th century. Beginning in the 30s, if one wanted to open a bagel shop in Manhattan, one had no option but to employ union bakers. Members had a reputation for being fierce, and those who didn’t comply with their stipulations received threats and boycotts.

The Good Life of a Unionized Baker

By keeping the knowledge of the bagel under wraps and urging their customers to buy from all-union shops, 338 members could negotiate impressively high wages.

Speaking with the New York Times in the early 60s, member Benny Greengrass reported an estimated base pay of $144 for a 37-hour work week for bench men and $150 for oven men (an estimated $65,000 annual salary today), with a chance for overtime. Bakers could make from $250 to $2,000 in a busy workweek with their high pay rate; employees also got dental, vision, and medical care, three weeks of annual leave, 11 days of holiday observance, and 24 free bagels every day they worked.

Bakers renegotiated their contracts annually, and if it wasn’t up to their expectations, they went off strike, plunging New York into a “bagel famine.” In the 1950s alone, bakers struck on two separate occasions: once in December of 1951, when 32 of the 34 bakeries closed, leaving shelves completely bare and food sales down by 50 percent, and in 1957, when 350 members went on strike and forced Brooklyn’s Pechter Baking Company to give away almost $20,000 worth of stock ($165,000 today).

Their biggest strike, though, took place in February 1962. With nearly unlimited control over the market, workers struck for 29 days and reduced the city’s bagel supply by 85 percent, leaving the assumption that bagel bakers were untouchable.

The Modern Beginning of a Traditional End

Early in the union’s creation, members of 338 agreed to strike down any attempt to automate the bagel-making process. Their traditionally made dough proved too challenging for machines, and the hand-made process gave the bagel a certain quality that consumers loved. However, as New York became known as “the bagel center of the free world” and union bakers produced up to 250,000 bagels daily, modernism steadily crept into the industry.

It started with the introduction of revolving ovens, which immediately increased production rates and moved bakeries from the basement to the sights of hungry customers. With the new view, bagels were being sold directly to consumers, prompting the start of the union’s downfall.

A California Math Teacher Kills A New York Union

Unbeknownst to Jewish bakers on the East Coast, the final nail in the coffin came from Daniel Thompson, a California math teacher in the late 1950s.

Thompson, the son of a baker, dedicated part of his career in 1950 to inventing an automatic bagel-making machine, something his father had been attempting for most of his life. By 1961, Thompson had cracked the code on his invention and successfully patented “The Thomas Bagel Machine.”

Five years after the machine’s initial construction, Thompson successfully leased the perfected design to Murray Lender, the son of Harry Lender, the founder of Lender’s Bagels. Even though the machine created bagels that lacked the artisanal qualities of the original, it could produce bagels four times as cheap, which, in Lender’s book, meant an opportunity to bring bagels to the mass market.

Soon after, Lender’s Bagels began selling mass-produced bagged and frozen bagels in supermarkets across the U.S., bringing the “exotic” food to new homes.

As more commercially made bagels found their way into stores across the city, union workers tried to hold out as long as they could, pleading to customers not to buy the mass-produced abomination—an effort that ultimately failed.

Bagel Bakers’ Local 338’s Demise

The union initiated a last strike attempt in 1967 but barely made waves on the market. This failure confirmed to the Jewish bakers that they had been officially replaced by machines, that American consumers valued cost and convenience over their traditional methods, and that their glory days were over.

Slowly and quietly, the union began dissolving. Some members moved from the city to open their shops, while others left the baking industry for good.

By 1971, the bakery workers completely abandoned the union’s independent efforts, and Local 338 had merged into a broader baker’s union.

Within the span of a few decades, New York bagel bakers went from exploited workers to form one of the most vital labor unions during the 20th century, a feat that was both new and risky for new citizens of the country.

Local 338 not only paved the way for making bagels a mainstream food in the U.S., but their strong-willed efforts also stood as a testament to equal rights for all, which we’re still fighting for today.

One Nation Under Dish covers in-depth history of the world’s most amazing food, drink cultural practices. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.